A Guide to Healthy Communication

M. Irons / Dr. Ron Burks from material presented at Wellspring Retreat and Resource Center in 1997.

Wellspring

Steve and I went to Wellspring Retreat and Resource Center for a week in the spring of 1997. Dr. Ron Burks met with us for two hours every morning and tutored us in the dynamics of cult relationships. Even though we had been out of the Assembly for eight years, were attending a good church, had read a lot of good books on spiritual abuse, and Steve had written several articles on the problems with George Geftakys, those sessions with Dr. Burks opened our eyes in a completely new way to what we had experienced in the Assembly and how it was still effecting us. Dr. Burks himself had been a leader for seventeen years in The Great Commission International, a cultic Christian shepherding ministry that was similar in many ways to the Assembly. He knew what he was talking about.

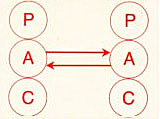

There is an imbalance of power in cultic groups. Leaders assume an extra-Biblical level of authority, and exercise an unethical degree of influence over followers. Dr. Burks uses the Transactional Analysis model to describe the life-positions people are pressed into in such a system.

A Typical Assembly Interaction

Leading Brother: “So, brother, has the Lord shown you the need to be active for Him in the outreach tomorrow night?"

Ordinary Saint: "Well, tomorrow I'm talking with my kid's teacher after the PTA meeting. I don't think it should wait.”

Leading Brother: “I am trying to be reasonable, brother, and you are just demonstrating that you're not entreatable. I think you should repent of your bad attitude and listen to what the Lord is clearly trying to show you.”

Ordinary Saint doesn't know what to say, and the Leading Brother starts talking to someone else.

This fictional exchange is from the article, "Mind Control." It shows the typical Assembly dynamics of domination, coercion and black-and-white thinking on the part of the Leading Brother, and victimized passivity on the part of the Ordinary Saint. It was the accepted thing, the expected thing. Anyone in any kind of leadership position - - Leading Brother, Children's Hour leader, husband, etc. - could be expected to get in your face in a stern disapproving manner at any time over any issue, no matter how petty, inconsequential or private. You felt guilty and slunk away licking your wounds. But your self-esteem would be rescued the next time you discipled a new recruit, saving them from a life of sin or the ignorance of worldly Christianity.

Lots of folks who were in the Assembly have come away with this pattern ingrained in their interactions with others, careening from persecutor to victim to rescuer, rarely in a balanced rational adult frame of mind. Steve and I were still like that eight years after we left the Assembly. We felt the disfunction but were helpless to understand it and change. Dr. Burks' presentation was complex, and took several hours to explain, but the outcome of understanding how to change our patterns of relating to people was worth it.

Overview of the Model Used at Wellspring

There are four main aspects to the model Dr. Burks used to help us understand Assembly dynamics. The first aspect covers the components of personality, in terms of the different "modes" or frame of mind in which people operate in various situations.

The second aspect is a description of the four basic life-positions that can be taken, depending on which component of personality is running things at the moment.

The third aspect is a look at the kinds of damaging interpersonal communications that result when people are operating from negative life-positions.

The fourth aspect is how this is all correlated with brain biology. This is key to understanding what happened to you in an abusive authoritarian environment, and how to get over it. Believer it or not, an environment characterized by negative life-positions actually changes the way your brain functions. And it's not for the better!

The Three Components of Personality

Basically, as human beings we operate in the world with a combination of three components:

- The input we received growing up, called, in this model, the Parent.

- Our natural makeup and how we responded to that input, called the Child.

- How well we make sense of it all and guide ourselves by informed objectivity, called the Adult.

The Parent is made up of the basic rules of life that have been internalized from one's parents. Parents nurture, and they also correct, so there are both positive and negative messages in the parent part of one's personality. Hopefully, there are lots of "You are loved and you're a valuable person" messages. Usually there are lots of "oughts" and "shoulds" and, "You don't measure up." The nurturing side of the Parent part of us cares for others, is encouraging and appreciative. The critical side of the Parent is negative and controlling. Negative parent messages may be extremely powerful.

The Child is the the natural person as we were born--spontaneous, fun-loving, intuitive, inquisitive, sensuous, mischievous, self-centered, joyful, compliant. The free Child is not limited by a concept of right and wrong--the basic creed of the Child is, “If it feels good, do it.” In the Child part of the personality are the ways the child coped with parental training, whether it was good or bad. Unresolved negative input caused the child to feel victimized and guilty. The Child part of us has become contaminated by this negative adaptation, which may also be extremely powerful--in some cases, the child felt that survival depended on it.

The Adult is the objective critical-thinking component that examines data and makes decisions based on logic. For example, the Adult will determine that when criticism or correction is needed, the Parent component will be more effective in nurturing mode. The Adult will ensure that appropriate correction is modulated with gentleness and empathy. In another situation, the Adult may give rein to the enthusiastic, creative Child but will set limits to keep the fun from degenerating into thoughtlessness and injury.

Ideally, in adulthood we operate primarily out of the adult, the nurturing parent and the free child—with the Adult always in charge. The adult is objective and sets appropriate limits. The nurturing parent is warm, caring, respectful, OK. The fun-loving free child is OK and safe because the adult is defining appropriateness for both the child and the parent. The person is OK with himself and with others--caring, fun to be around, respectful, and appropriate. This translates to kind, respectful interactions and conversations.

Our "typical Assembly interaction" shows the Leading Brother in Critical Parent mode--disapproving, controlling, self-assured that his dominance and black-and-white thinking is okay. Ordinary Saint is in Victim mode, feeling guilty and powerless, but unconvinced.

The Four Basic Life Positions

At any given moment, we are in one of the four basic life positions, and we move back and forth between them:

1. I’m OK and you’re OK.

2. I’m not OK, but you’re OK.

3. I’m OK, but you’re not OK.

4. I’m not OK and you’re not OK either.

The first position is that of the growing person. “I am an OK person, and so are you.” There is self acceptance and acceptance of others. There is self respect and respect for others. There is emotional honesty and appropriate boundaries. (This has nothing to do with denying the existence of sin, by the way, an assertion made by GG in his scathing remarks on the book, I'm OK, You're OK, by Dr. Thomas Harris.)

This position is not naive, idealistic or perfectionistic. The person takes responsibility for his own life. He cares about other people, but he doesn’t assume responsibility for them. A maxim to keep in mind is, “My needs are as important as the other persons--not more important, but of equal importance.” In transactions between growing persons both parties are acting and speaking from the Adult position

The second position is the victim. “I am not an OK person, but you are. I need you to tell me what to do and take care of me." This is a dependent, helpless position--the victim feels he is not a worthwhile person, so bad things happen to him. The brain chemistry of victim mode shuts down cognitive ability, so the person acts out of emotion instead of reason.

The third position is the persecutor. “I’m OK, but you are not. You need what I’ve got, because you’re not OK.” In the Assembly, this position is held by leaders, who believe, “Because you’re not OK, it doesn’t matter what I do to you, and because I am OK, it’s all for your good.” Assembly members begin to take on this position, also, as they identify with the group and attempt to influence others by recruiting, shepherding, etc. Empathy and conscience are repressed in persecutor mode. Judgmentalism and contempt are fostered and become predominant feelings.

The fourth position is rescuer. “I’m not OK, and you’re not OK either. Because you’re not OK, I have to take responsibility for you, and because I’m not OK, it doesn’t matter what happens to me while I'm rescuing you.” Rescuing confirms to rescuees that they are not OK and that they are incapable of taking care of themselves. The brain chemistry of the rescuer shuts down feelings, so there isn’t awareness of personal needs or emotional cues. A person may shift from Victim to Rescuer because the emotional numbing is a relief.

Dr. Burks convinced me that one of the goals of recovery from the Assembly experience is to get to the "I’m OK, you’re OK" position and start growing again:

** Stop thinking that I have something everyone else needs (Rescuer)

** Stop communicating that others need to listen to me for their own good (Persecutor)

** Stop reacting to Rescuers and Persecutors alike with silent or whining passivity (Victim)

** Work on communications that are respectful and kind, but also thoughtful and principled (Adult).

Here is a great article, with graphics, on ending the triangulation of the Drama Triangle.